The trail to Silver Peak is four and a half miles. With its trailhead just up the road from my campsite, and beginning with an ascent of a ridge just behind my corral, the Silver Peak Trail #280 has an elevation gain of three thousand feet. It is a true test of endurance. Many locals hike the "first mile to the first gate" as exercise. Despite the thousands of feet of vertical ascent ahead, this switchback-free stretch is one of the toughest along the trail, states the trail description.

Even though I can shortcut the trailhead and climb the hill behind the corral to access the trail, I waited until this morning to visit it for the first time of the year. I did not heed the forecast. Two days ago monsoon season officially kicked off with localized thunderstorms that brought close to an inch of rain to Portal, Arizona just outside the mountains, but curiously barely registered on the Southwestern Research Station (SWRS) weather monitor three miles up canyon from me.

The North American monsoon generally affects the area from the second week of July until as late as mid-September. It is also known by locally biased names like "Arizona Monsoon, New Mexico Monsoon, and Southwest Monsoon", but North American is most appropriate as the pronounced increase in thunderstorms and rainfall is seen over much of the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico and is geographically centered over Mexico's Sierra Madre Occidental range. Wind patterns reverse in summer as the land that has been intensely heated by the sun (thermal low pressure) causes the prevailing winds to start to flow (high pressure) from moist oceanic areas to the arid landscape. Monsoon season begins as early as late May in Mexico and arrives in Arizona and New Mexico as summer begins and June gives way to July. As temperature cools in September and drier conditions prevail, the monsoons lose their energy.

This year has been particularly dry in southeastern Arizona. Locals tell me how there was "no winter". Snow and rain were scarce. The SWRS reported one day with 0.13" precipitation in January. One significant day of rain in February brought that monthly total to just under two inches. March had one day of rainfall (0.47"), and April and May were completely dry. When a fluke rainstorm fell for two days in mid-June it was a gift from the skies, but it was due to a tropical storm off the Gulf of Mexico and didn't herald the beginning of our rainy season. But when less than a quarter inch fell on June 29 at SWRS, but closer to an inch was seen in Portal, residents rejoiced. The monsoons wouldn't truly begin for another ten days or so, but the ocotillo greened and then bloomed, the grass at the VIC grew a bit greener and baby lizards emerged.

The Fingers can be partially seen at right

As I passed the first 'pedestrian gate' on Silver Peak Trail this morning, I was posting scenic snapshots and videos to my Instagram story. I then looked up at The Fingers, a rocky hand reaching to the sky from the peaks, and saw the storm that was about to envelop me. I posted both my apprehension to continue on and that caution wasn't my style, and then had only moments to find a large boulder formation to protect my camera in before I was soaked and scurrying down trail to find any tree that would offer cover. Torrential rain fell and thunder boomed as lightning cracked. It would be more than an hour before I crawled out from under that pinyon pine and I was saturated. I looked back up at The Fingers and saw a waterfall had formed on an adjacent steep cliff. I had been upset with myself for not carrying my large camera bag, which as a rainfly, or at least not having a trash bag in my small knapsack to protect my camera and lens. I retrieved the lens from beneath the boulder overhang and started down the trail, but the rain started again. Once again, I huddled beneath the mediocre cover of a scraggly desert pine and this time tried to make room in my pack for the camera. It wasn't until I got back to camp that I realized that I am a bonehead and my Lowe camera knapsack actually does have a rainfly. Not that it would have mattered. When the storm's darkness came over the mountain and down the trail I had no choice but to become drenched squatting anywhere I could.

But let's go back almost two weeks to the last day of June and a different, and much drier, mountain trail. It was a day I will always remember. The Trans-mountain Road, or Forest Road 42, climbs Cave Creek Canyon up the mountain to Onion Saddle, where you can crest the northern Chiricahuas and descend Pinery (Pine) Canyon to Chiricahua National Monument or choose to drive south toward Rustler and Barfoot Parks. Onion Saddle is about a dozen miles up the mountain from Cave Creek Canyon, much of it on winding, primitive road with numerous single-lane switchbacks. The pavement ends just three miles up canyon from the Visitor Center, passes SWRS three-quarters of a mile later, and then the primitive road ascends from 5400 feet to 7600 feet at Onion Saddle. There you either drop down the mountain towards the Monument and paved roads north to Willcox, or continue to climb to Rustler Park (8500 ft) and Barfoot Park (8200 ft), where a network of trails centered around the Crest Trail (#270) runs along the peaks (hence, "crest") to the apogee at Chiricahua Peak (9700 ft). During the Horseshoe 2 Fire of 2011, much of this montane area burned and the landscape and associated trails continue to recover. Volunteer trail crews hike with chainsaws to part trees that continue to fall over the many paths that explore this alpine region.

With the monsoons yet to arrive, June is the hottest month of the year. The temperature can be as much as fifteen degrees (Fahrenheit) cooler at Barfoot and Rustler than down in Cave Creek Canyon, which itself is often as much as ten degrees cooler than the desert just outside the mountains. Barfoot and Rustler Parks are set in mixed conifer forest and the landscape is more Rocky Mountains than Sonoran or Chihuahuan Desert. Adding to the allure, they are home to montane wildlife like Steller's Jays, Mexican Chickadees, Cliff Chipmunks and, for me sexiest of all, the small, mountain rattlesnake - the Twin-spotted. Although the Trans-mountain Road is steep and rugged, with amazing vistas mixed with scary, sheer drop-offs along its single vehicle width, I ascend it as often as I can to reach cooler climes and gorgeous surroundings.

My long-time readers will remember stories about this diminutive rattlesnake from last year's blog entry on searching the expansive high elevation talus slopes that form its habitat. Those with keen memories will also recall that I had quite the tumble on the sharp rock causing blood loss to my legs and body fracture to my ring flash. This year I have confined my exploration to the base of the rock slides and adjacent wooded areas and meadows. But discussing trails with both visitors and locals had me intrigued to explore the high altitude trails of the region.

I had tried to access Barfoot a couple of days earlier, but as I drove from Barfoot Junction where you head left toward Rustler or right for Barfoot I crossed the cattle guard and was stopped by several real-life cowboys ranging cattle. It was a curious sight above 8000 ft. and I couldn't recall seeing any cattle this high before. But, there I sat, perplexed, watching a half dozen dogs circling four head of cattle lined up on the road with three or more people in Stetsons, boots and demin on horseback directing the dance. After I sat there some time, one horseman came my way and I soon realized that it was a boy no more than 14. I swear he even had tobacco in his mouth when he tipped his hat to me. Pulling his horse up beside my truck, he told me that it would be awhile. He said if he let the cattle break free they might not be able to round them up again. No worries, I told him, and I backed down the road and eventually moved on to Rustler to photograph the elusive and nervous Cliff Chipmunk.

But the trail that continued to interest me was Barfoot Lookout Trail. Although I knew that the fire lookout cabin that was built in 1935 by the Civilian Conservation Corps no longer exists, after being burned during the 2011 Horseshoe 2 Fire, the summit of Buena Vista Peak (8800 ft) now has a little stone-walled viewing area and offers a breathtaking panorama of the surrounding mountains overlooking prime rattlesnake habitat. There also is a solar panel station and radio repeater and the foundation of the old cabin and outhouse may be seen.

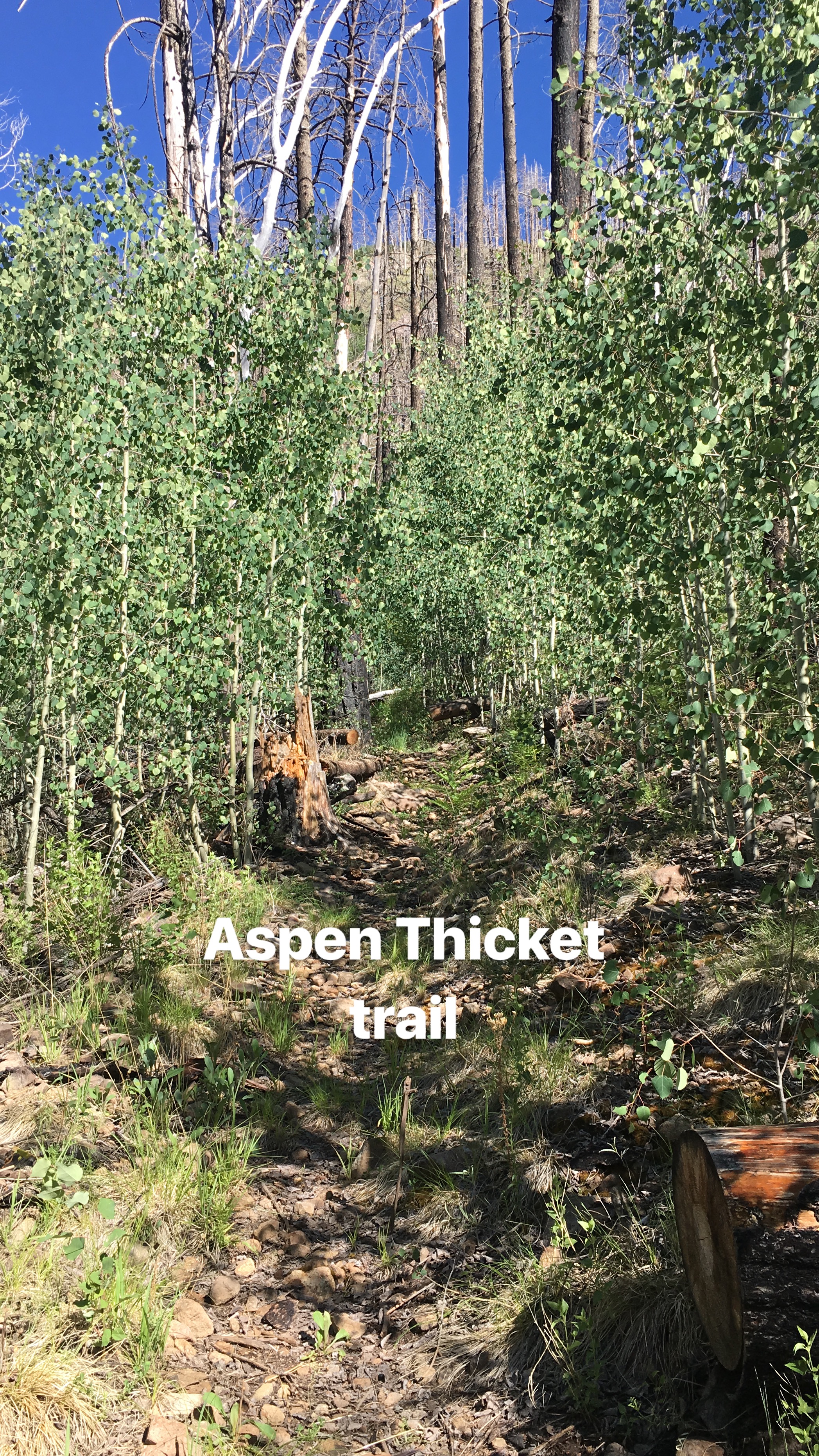

Although the Crest Trail itself intersects the Barfoot Lookout Trail, I would be starting at the lower terminus near Barfoot Meadow. It begins to climb adjacent to Barfoot Spring and after passing through a stand of burned timber reaches a thicket of quaking aspen saplings. Eventually the trail bends sharply to the left and the last three or four hundred yards climbs the mountainside without any switchbacks. Once you reach Barfoot Saddle you are at the Crest Trail junction where I chose to make the climb to Buena Vista Peak.

Along the way I would see more Yellow-eyed Juncos, a bird that thrives at the mountain tops, baby Yarrow's Mountain Spiny Lizards and, during my initial descent, Broad-tailed Hummingbirds feeding at the Bearlip Penstemon flowers abundant on the mountain slope.

The road up to Barfoot (FR 357) looking down east from the "lookout"

Looking west down on whence I came ...

Just enjoying the trail, reaching the summit, and meditating on the spectacular vistas would have made for a wonderful Saturday. But the best was still to come. At some undisclosed point during my descent, I would stumble upon what I consider the jewel of the mountains - The Twin-spotted Rattlesnake. This protected species is a denizen of talus slopes and rock slides, but is known to be found away from much rock in the vicinity of rotting wood and other forest cover beneath the conifers. A streak of silver flashed upon the trail. I leaped forward, almost stumbling over a log or two. I am sure comedy ensued, but not even a bear was present to witness my grace. Disappearing beneath a rock on the other side of the trail, the cooperative snake gave me time to toss off backpack, camera, binoculars, hat and probably even my glasses as I tried to switch from long bird lens to macro setup in seconds. I didn't have an external flash so the lowly built-in speedlight would have to suffice. I think I may have had enough time to chug some water and wipe my brow before I kneeled beside the rock and tried to catch my breath. I had had only a momentary glimpse, but there was no mistaking that this must be a Twin-spotted Rattlesnake. The species only rarely reaches two feet in length, and this snake was every bit of it, maybe more. Nothing else was silver-grey and little else lives at 8500 feet elevation. As a protected species, it is unlawful to pursue, harass, etc. and certainly restrain or collect, so I wanted to disturb as little as possible as technically even flipping the rock would be pursuing. But flip I did, and beneath was an adult Twin-spot as big as they come and suprisingly cooperative. I wished I could pose it on rock for a better photographic setting, but I snapped a few images and then videotaped it with my iPhone as it slithered into the forest.

“The Twin-spotted Rattlesnake (Crotalus pricei) is the smallest American rattlesnake and occurs at the highest altitude. It is a protected species found in the United States only in Arizona’s Chiricahua, Huachuca, Santa Rita and Pinaleno Mountains. Our western subspecies ranges south into Mexico (Sierra Madre Occidental) with an isolated subspecies being found in northeastern Mexico (Sierra Madre Oriental). Diminutive and slender, it is a silver, blue-grey or greyish-brown rattlesnake that only rarely reaches two feet in length. Its head is not as broad as that of most rattlesnakes, and with paired dorsal blotches that give it its name, limited range, specific habitat, and orange color of the newest rattle segments, it cannot be confused with any other snake. The Twin-spotted Rattlesnake is primarily known from Petran Montane Conifer Forest at elevations of 7500-9000 feet where it is generally an inhabitant of expansive talus slopes and rocky outcrops, but this photo depicts an example of a snake found in adjacent alpine forest among rotting logs and rocks. I encountered this very large adult along a trail at 8500’ while descending from one of Chiricahua’s peaks. The Twin-spotted Rattlesnake is active during the daytime and primarily feeds on the Mountain Spiny Lizard (Sceloporus jarrovii). Its young are born in summer when baby lizards are abundant in its rocky home. July and August is also the time when breeding takes place. Like other montane rattlesnakes, it delays fertilization of its ova and development takes place very slowly, resulting in birth of a handful of small live young the following summer. ”

In closing, finally, I'd like to apologize for not posting for three weeks and make you aware of a Chiricahua Mountain Wildlife slideshow video I have published to my YouTube Channel. It is a compilation of many of my wildlife images captured from April through June 2018. Please enjoy. Cheers, MJ